# Unraveling Solar Mysteries: The Sun's Magnetic Behavior Explained

Written on

Chapter 1: Understanding the Sun's Magnetic Activity

Recent research has unveiled that the peculiar physics observed on the Sun may shed light on the enigmas surrounding its magnetic field. Sunspots located close to the Sun's surface are influenced by an unanticipated magnetic instability.

The Sun appears as a dynamic sphere of plasma (ionized gas), rotating around its axis. Electric currents moving within the Sun generate a vast magnetic field, which drives the formation of sunspots. Nevertheless, the underlying mechanisms remain largely unclear.

A new study proposes that an unknown process may be taking place within this plasma, potentially crucial for understanding the Sun’s magnetic behavior.

Plasma ascends from the Sun's surface due to magnetic field movements. Image credit: NASA/SDO

Section 1.1: The Rotation of the Sun

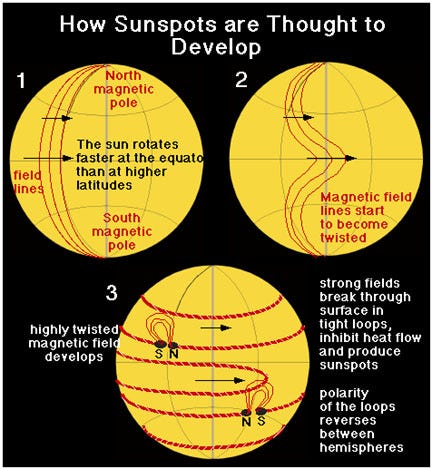

The Sun exhibits varying rotation speeds: it spins faster at the equator than at the poles. Near the equator, it completes a rotation every 25 days, while polar regions take between 33 to 35 days. This differential rotation stretches magnetic field lines, which can eventually rupture, giving rise to sunspots.

Sunspots, known to many as a prominent feature of the Sun, typically emerge around 30 degrees north and south of the equator, gradually migrating toward the center. As the solar cycle progresses over 11 years, the number of visible sunspots increases, with more appearing closer to the equator. Consequently, most sunspots are concentrated near the Sun's equator, where magnetic activity is most intense.

The butterfly diagram illustrates the increasing number of sunspots forming closer to the equator over time. Image credit: NASA

Section 1.2: Magnetorotational Instability

Magnetorotational instability (MRI) is a phenomenon that leads to instabilities in electrically conductive fluids and gases. Recent findings from a team of international researchers suggest a new form of MRI, termed Super HMRI, which has not been accounted for in existing solar dynamo theories, may help clarify the magnetic processes occurring in the Sun.

"This new instability could significantly contribute to the generation of the Sun's magnetic field. However, to validate this, we must conduct more complex numerical calculations," explains Dr. Frank Stefani from the Institute of Fluid Dynamics at Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR).

Magnetic instabilities influence numerous processes in natural systems throughout the universe. For instance, the formation of stars and planets from gaseous and dusty disks relies on such magnetic fields. Variations in these fields result in turbulence, promoting mass accumulation in certain areas, ultimately forming the core of celestial bodies.

Differential rotation leads to layered magnetic fields that can rupture, resulting in sunspots. Public domain image.

Chapter 2: The Equator's Unique Behavior

However, near the solar equator, plasma behaves contrarily; outer layers move more quickly than inner layers. Researchers from Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR), the University of Leeds, and the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam (AIP) have reported these findings.

The team investigated whether the proposed magnetic instabilities could develop under the unique conditions expected near the solar equator. Although their initial experiments were successful, they modeled a version of the Sun lacking much of the actual differential rotation.

"Astrophysicists and climate researchers continue to seek a deeper understanding of sunspot cycles. The discovery of the ‘Super HMRI’ may represent a significant advancement. We are eager to explore this further," states Prof. Günther Rüdiger from the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam (AIP).

As Charles Dickens eloquently noted, "The sun, — the bright sun, that brings back, not light alone, but new life, and hope, and freshness to man — burst upon the crowded city in clear and radiant glory."

The magnetic anomalies examined in this study may influence the entire magnetic field of the Sun, which reverses its poles approximately every 11 years. During these flips, the sunspot cycle renews, with reversed magnetic poles from the previous cycle. Thus, the complete sunspot cycle spans roughly 22 years before returning to its original state.

In 2006, this research team suggested that these magnetic instabilities could theoretically arise in the chaotic conditions predicted near the solar equator. They now plan to build on that success by designing an experimental facility — The DREsden Sodium facility for DYNamo and thermohydraulic studies (DRESDYN) — to further test their hypotheses.

The findings of this recent study were published in Physical Review Fluids.

Did you enjoy this article? Subscribe to The Cosmic Companion Newsletter!

This video features an astrophysicist discussing the ten most intriguing unsolved mysteries of the cosmos, including insights into the Sun's behavior.

In this video, experts explain the impending flip of the Sun's magnetic field and the potential challenges it poses, based on NASA's findings.