The Decline of Venezuela's Glaciers: A Historical Perspective

Written on

Chapter 1: A Glimpse into Venezuela's Skiing History

Once known for its skiing competitions, Venezuela has undergone a dramatic transformation in less than 70 years.

In the 1950s and 60s, against the backdrop of being just 8 degrees north of the equator, two international ski championships took place on Pico Espejo in the Sierra Nevada de Mérida.

The inaugural National Ski Championship was held on October 12, 1956, featuring a 250-meter slope descending from 4,850 to 4,600 meters above sea level. It attracted 28 competitors from nine different nations, including four women. The Sierra was compared to the Swiss Alps, with many anticipating a bright future for this unique equatorial winter haven. However, heavy snowfall on the championship day led to the cancellation of practice sessions, and the conditions never improved thereafter.

In March 1960, the Mérida Cable Car, which was the highest in the world at that time, opened up new possibilities. Ski seasons spanned from May to October, and a second skiing competition was held from October 25 to 30, 1961, featuring speed and style trials for a unified classification.

With clear weather conditions, participants could admire the connected peaks of the Humboldt and Bonpland glaciers. Austrian-Venezuelan Carlos Feix won the competition, joined on the podium by Venezuelan Michel Carpio Méndez and Czech-Venezuelan Tomás Sensky. Unfortunately, just a decade later, there would be insufficient snow left for skiing on Pico Espejo.

Chapter 2: The Loss of Glaciers

The first video titled "Venezuela Likely the First Nation to Lose All Its Glaciers" highlights the alarming situation regarding glacier disappearance in Venezuela.

Glaciers cover 10% of the Earth's surface and store nearly 70% of the planet's fresh water. The Andes Mountains once housed 4.5% of these glaciers, but today, the Humboldt Glacier in the Sierra Nevada de Mérida is no longer classified as a glacier but as an ice field, due to its reduced size.

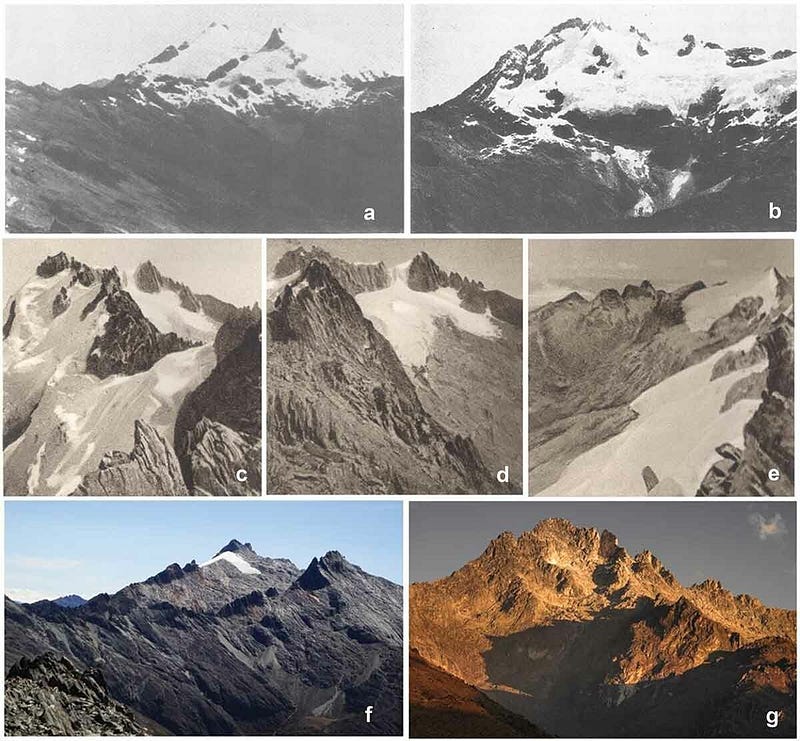

Consequently, Venezuela has officially become glacier-free, a unique occurrence in modern history, not just within the Andes but globally. At the dawn of the 21st century, Venezuela boasted six glaciers in the Sierra Nevada. By 2011, only the Humboldt Glacier remained.

Originally, it was expected that the Humboldt Glacier would last another decade. However, a 2020 study by Llambi et al. indicated it had decreased far more rapidly than anticipated between 2015 and 2016. Political unrest in Venezuela hindered scientific monitoring, but upon returning in December 2023, researchers discovered that the glacier had shrunk from 450 hectares to possibly two or fewer.

“The glacier at Humboldt lacks an accumulation zone and is solely losing surface area, with no potential for accumulation or growth,” stated Llambi.

Though there is no universal standard for what constitutes a glacier, 10 hectares is often used as a benchmark, leading to its reclassification.

The second video, "How did Venezuela's Humboldt glacier shrink to an ice field?" explains the causes behind the glacier's rapid decline.

Chapter 3: A Reflection on Global Glacier Trends

The conclusion of the Little Ice Age, which allowed for ice walks from Manhattan to Staten Island, resulted in the disappearance of many glaciers—a trend expected for lower-altitude regions. Despite standing at altitudes of 4,000 to 5,000 meters, Venezuela's glaciers were not spared. The entire nation has recorded significant temperature anomalies of +3°C to +4°C, leading to their complete disappearance.

Llambi warns that Venezuela is a precursor for what will soon unfold from north to south across South America, impacting Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia as glaciers continue to recede. This phenomenon isn't confined to South America; climatologist Maximiliano Herrera predicts that Indonesia, Mexico, and Slovenia are next in line to be glacier-free.

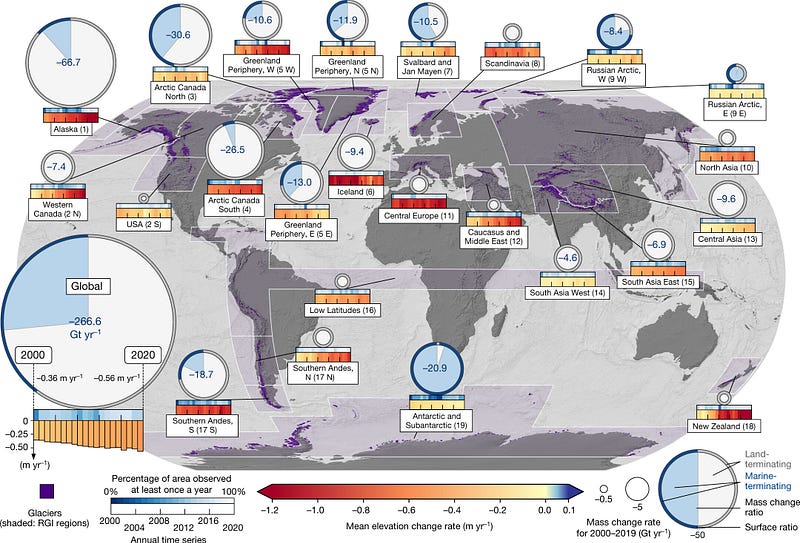

This reality is alarming, particularly as a study led by glacier and sea-level change expert David Rounce indicates that global glaciers could lose up to 40% of their mass, with nearly half potentially vanishing by 2100, even with a temperature rise of just 1.5°C. If temperatures were to reach 2.7°C, most glaciers in Central Europe, western Canada, and Alaska would face a similar fate.

Rounce asserts, “Regardless of temperature increases, glaciers will inevitably experience significant loss.”

Adding to this, a study by Hugonnet et al. revealed that glaciers outside the ice sheet peripheries have seen a doubling in thinning rates over the last twenty years. The warming zones are expanding due to climate change, and with record average temperatures for 11 consecutive months, the retreat of glaciers is set to accelerate.

Chapter 4: The Implications of Glacier Loss

While Venezuelan glaciers were not major water sources like those in Peru, their disappearance has broader implications that extend beyond just the ice. The impact on ecosystems, cultural identity, and tourism activities is substantial.

In a last-ditch effort to save the remaining ice, local authorities attempted to cover the glacier with a thermal blanket to prevent further melting. However, this effort was ultimately unsuccessful. Once a glacier is lost, the ground heats up, making it too warm for ice formation in the summer. Additionally, the covering posed a risk of contaminating the environment with plastic as it deteriorated.

This situation can be likened to lying under a short blanket: initially comfortable, but as temperatures drop, one must adjust, leaving certain areas exposed. Venezuela's dependence on fossil fuel extraction as an OPEC member exemplifies this short-blanket dilemma—providing economic benefits while simultaneously contributing to global warming and its environmental consequences.

Venezuela is not the only nation to bear responsibility. A recent UN report indicates that major fossil fuel producers are planning expansions that could surpass the planet's carbon budget by a factor of two. This situation threatens humanity's future. While some losses are unavoidable, any efforts to reduce CO2 emissions may help protect other glaciers and prevent a cascade of adverse effects.

Be vocal in advocating for change.

Thank you for your attentive reading and support! Join the 500+ Antarctic Sapiens community for weekly insights.