Understanding ADHD: From Childhood to Adulthood

Written on

Chapter 1: Overview of ADHD

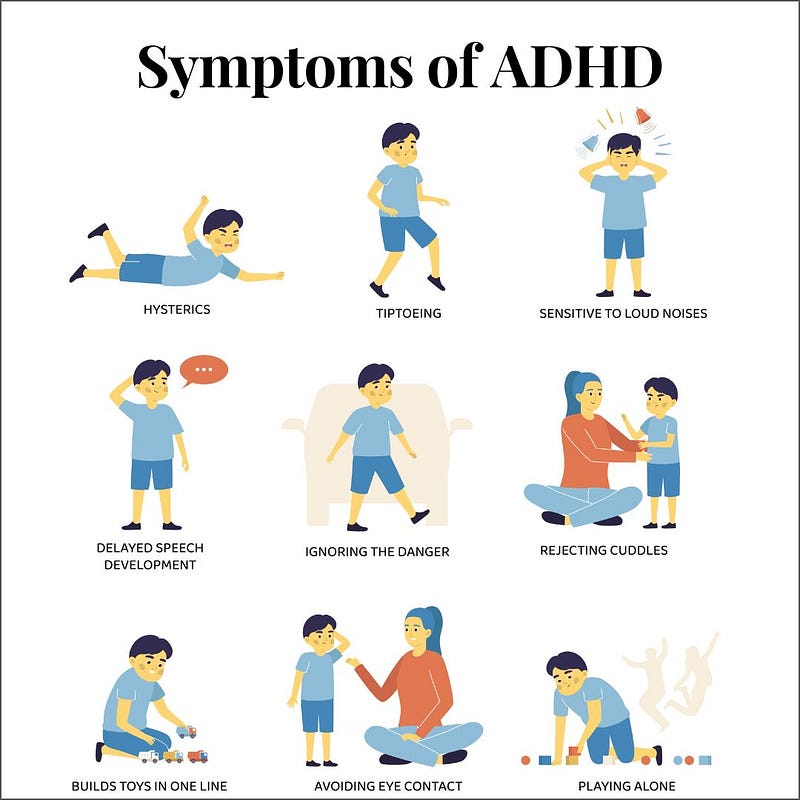

Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) ranks among the most prevalent neuropsychiatric disorders, typically emerging in childhood and frequently enduring into adulthood. This condition is marked by significant dysfunction and morbidity. Although advancements have been made in understanding its neurobiological underpinnings, the diagnosis of ADHD continues to rely primarily on observed behavioral symptoms, including inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity. This chapter aims to outline the diagnostic process while addressing ongoing debates surrounding ADHD diagnoses. We will also explore how the disorder presents across various life stages, investigate patterns of comorbidity, and assess predictors of long-term outcomes. Lastly, we will identify the challenges that future classification systems must tackle to improve the accuracy and validity of ADHD diagnoses.

ADHD in Early Development

Characterized by significant symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, ADHD is one of the most extensively researched conditions in medicine (Goldman et al., 1998). It is recognized as a multifactorial developmental neuropsychiatric disorder, influenced by genetic factors and neurobiological irregularities. Epidemiological studies estimate a worldwide prevalence of 5.29% among individuals under 18 (Polanczyk et al., 2007), while a recent meta-analysis indicated a 2.5% prevalence rate in adults (Simon et al., 2009).

Contrary to previous beliefs that ADHD would resolve by adolescence, longitudinal studies reveal that the disorder often continues into adulthood (Biederman et al., 2010). ADHD frequently coexists with other psychiatric disorders, such as oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), conduct disorder (CD), learning disabilities, substance use disorders, and mood and anxiety disorders. The disorder also leads to compromised academic and social functioning, causing considerable emotional distress for affected individuals and their families.

Throughout various developmental stages, ADHD correlates with numerous adverse outcomes, often worsened by comorbid conditions. In children, this may manifest as poor school performance, low academic achievement, grade retention, and an elevated risk of suspension or expulsion. For adolescents, ADHD is linked to strained relationships with peers and family, school dropout, aggression, conduct issues, delinquency, and early substance abuse. In adults, common challenges include traffic accidents, speeding violations, difficulties in social relationships, marital strife, and job-related issues (Biederman et al., 2010; Fischer et al., 2007; Kessler et al., 2006; Nijmeijer et al., 2008). Thus, ADHD affects not only individual accomplishments but also various life areas, including family life, work, community engagement, romantic relationships, financial management, and leisure activities (Barkley & Murphy, 2010).

This video, titled "Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD/ADD) - causes, symptoms & pathology," explores the foundational aspects of ADHD, including its symptoms and potential causes.

ADHD in Preschool Children

Although referrals for ADHD evaluations primarily involve school-age children, early assessment is critical. Preschoolers with ADHD often face behavioral, social, familial, and academic challenges. Reports from parents and clinicians indicate a strong connection between early behavioral issues and future difficulties in school-aged children (Spira & Fischel, 2005). Young children with ADHD may demonstrate markedly deviant behavior, including poor focus, hyperactivity, restlessness, disobedience, and impaired social interactions. These disruptive behaviors are frequently accompanied by dysfunctional maternal-child interactions, which may further perpetuate these issues (DuPaul et al., 2001).

In addition to core symptoms of ADHD, many preschoolers exhibit developmental delays, impacting sensory, motor, language, and intellectual capabilities (Yochman et al., 2006). Consequently, these children often require increased access to remedial services such as speech, language, occupational, and physical therapy, and they are more likely to be enrolled in special education programs (Marks et al., 2009).

Despite being younger, preschool children with ADHD exhibit notable similarities to their older counterparts regarding impairments and psychiatric comorbidities. Research conducted by Wilens et al. (2002) found that these young children display significant dysfunction in academic, social, and overall functioning comparable to older children. Approximately half of the children in both age brackets experience mood disorders, with a trend indicating a higher prevalence of comorbid bipolar disorder among preschoolers (Wilens et al., 2002). A large-scale study involving 303 preschoolers diagnosed with ADHD revealed that 69.6% had comorbid disorders, with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), communication disorders, and anxiety disorders being the most prevalent (Posner et al., 2007).

It is suggested that challenging mother-child interactions and family stress may impede the development of effective coping mechanisms for managing problematic behavior, contributing to the persistence of ADHD symptoms (Chi & Hinshaw, 2002). Parents of children aged 3–5 with ADHD often experience heightened stress, exhibit more negative behaviors towards their children, and employ less adaptive coping strategies compared to parents of children without ADHD (DuPaul et al., 2001). Furthermore, mothers of preschool-aged children with ADHD report higher levels of depressive symptoms and a diminished sense of parental efficacy (Byrne et al., 1998).

ADHD in School-Age Children

Most school-age children with ADHD encounter significant obstacles in their academic performance and peer relationships (APA, 2000). The severity of these difficulties varies by subtype, with children exhibiting the combined subtype facing greater social impairments and peer rejection compared to those with only inattentive or hyperactive symptoms (Willcutt et al.). Both combined and inattentive subtypes show more academic challenges than those with hyperactivity alone (Gaub & Carlson, 1997). Approximately 30% of children with ADHD also have learning disabilities, and many underperform academically despite having average or above-average IQs (DuPaul & Stoner, 2003). These children have a higher likelihood of being suspended, expelled, or required to repeat grades, and they tend to have lower graduation rates (Loe & Feldman, 2007). Research indicates that these academic difficulties arise from ADHD itself rather than comorbid conditions, with neuropsychological deficits, such as impaired motor inhibition, contributing to early learning challenges exacerbated by disruptive behaviors (Hinshaw, 2003). Additionally, struggles with maintaining focus during classroom tasks and following instructions further inhibit academic success (DuPaul & Stoner, 2003).

The second video, "What is ADHD? - YouTube," provides a concise overview of ADHD, covering its definition, symptoms, and impact on individuals.

ADHD in Adults

Longitudinal studies indicate that ADHD persists into adulthood in approximately 65% of cases, with varying remission rates influenced by different definitions and the natural progression of the disorder (Barkley et al., 2002; Faraone et al., 2006). Even when individuals no longer meet the full criteria for symptoms, adults with a history of ADHD continue to exhibit higher levels of symptoms compared to the general population (Ramtekkar et al., 2010). The severity of childhood ADHD and the treatments received are predictive of persistence (Kessler et al., 2006).

ADHD in adults often coexists with other psychiatric conditions, with 38.3% experiencing mood disorders, 47.1% anxiety disorders, 15.2% substance use disorders, and 19.6% impulse-control disorders (Kessler et al., 2006). Emotional impulsivity, characterized by irritability and frustration, is prevalent and may account for ADHD's frequent comorbidity with other psychiatric issues, such as oppositional defiant disorder (Barkley & Fischer, 2010).

In adults, ADHD symptoms tend to be more subtle and varied; hyperactivity may manifest as a busy lifestyle, impulsivity may result in instability in relationships or jobs, and inattention can hinder tasks that require organization and prolonged focus. Common executive functioning deficits include procrastination and poor time management (Weiss & Weiss, 2004).

ADHD in Adolescents

Most children diagnosed with ADHD in elementary school continue to exhibit significant symptoms into adolescence, though hyperactivity often becomes less conspicuous with age (Faraone et al., 2006; Ramtekkar et al., 2010). As academic demands intensify in middle and high school, previously manageable issues may become more pronounced (Bussing et al., 2010). Adolescents with ADHD frequently experience increased peer rejection and have fewer close friendships, as social connections become more crucial (Bagwell et al., 2001).

Emotionally, adolescents with ADHD may display immaturity, struggle with emotional regulation, and experience outbursts of frustration and anger (Barkley & Fischer, 2010). About 50% of these adolescents also meet the criteria for oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) or conduct disorder (CD), which exacerbates their difficulties (Kutcher et al., 2004). ODD is characterized by hostile and defiant behaviors, while CD involves persistent antisocial actions such as aggression, theft, and rule-breaking, with CD being more prevalent in boys (Biederman et al., 2008). Many adolescents diagnosed with CD also have ADHD (Kutcher et al., 2004).